The Pont du Gard Most Tourists Never See

It boggles the mind to consider that the Pont du Gard’s sole purpose was to bring water to Nimes. But not for drinking. The purpose for constructing the 31-mile long aqueduct was to ensure that Nimes’ (then Nemausus) fountains would splash, the public baths would be filled to overflowing, and that water features everywhere would delight.

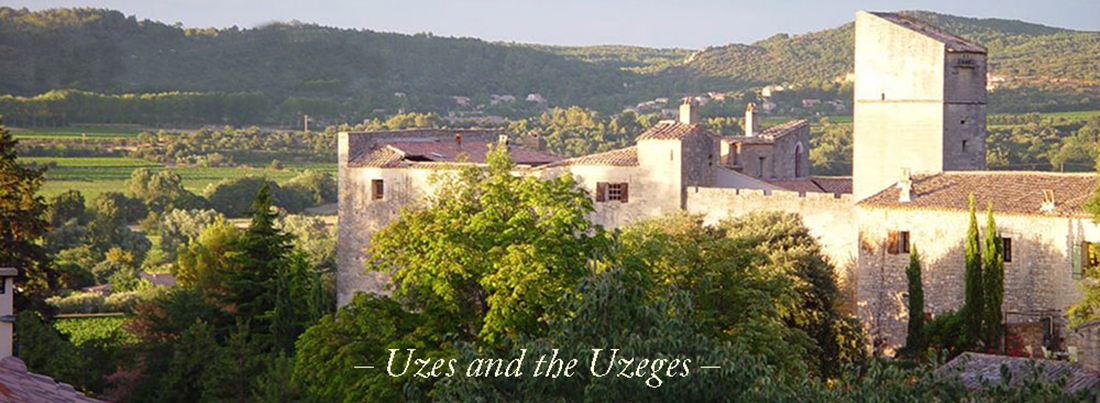

It has been calculated that more than 200,000 cubic yards of water flowed from Uzes to Nimes…a staggering amount.

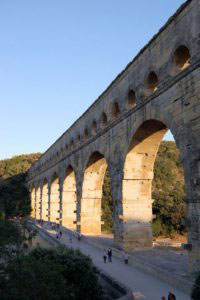

The bridge has three tiers, and water was only moved along the upper-most one.

It’s important to keep in mind that no pumps were used to keep the water flowing…it was all done with gravity. Roman engineers designed an ever-so-slight decline into the aqueduct (a gradient of only 1 in 18,241) which kept the waters slowly moving along.

And it’s equally amazing to consider that there’s not a drop of mortar in the construction. The bridge is entirely made of fitted stone.

There’s an interesting part of the Pont du Gard which played a role in Saint Siffret’s and the Chateau de la Commanderie’s history. And most people never realize they are walking on it.

Note the walkway (bridge) in the photo above. It was not part of the original aqueduct, but was added by the Doc de Rohan’s military engineers to transport their cannons across the river during the Wars of Religion of the 1500s. (Covered in Chapter 24: Ubi Sunt Qui Ante Nos Fuerent?; which explains why the church in Saint Siffret’s façade is pock-marked with musket and cannon ball holes.

The Duc de Rohan’s engineers were a bit clumsy about it, though, and trimmed the second tier of the Pont du Gard’s arches by as much as a third, damaging and weakening the structure in the process.

Things have definitely changed since we first visited. The Pont du Gard has since become one of France’s most visited sites. There’s a wonderful museum (admission is included with the price of entry) as well as an interesting art exhibition hall, where some very talented artists expose their works. And there are the requisite gift shops, restaurants and restrooms.

The Pont du Gard has grown up. But if you would like to see more of the aqueduct: the way it stood in the fields for centuries, then a shining example is not far away. Not many people know about it, and it is definitely worth a look.

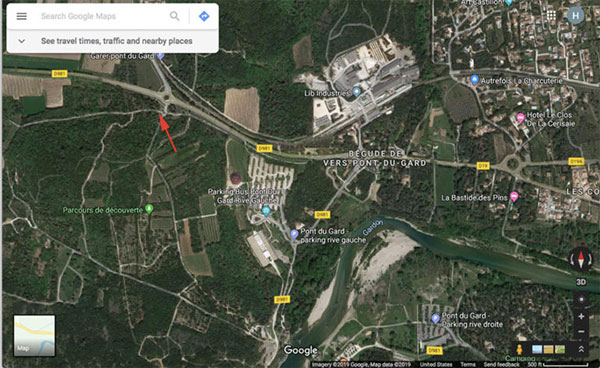

An unrestored section of the aqueduct lies only a few hundred yards away. Many people in Uzes don’t even know about it.

You are free to stroll along, entirely unconstrained, and admire the ruins (note the filled-in arches, which provided added strength).

TIPS:

• During peak tourist season, there is a son et lumiere show most nights. Linda says it is well worth seeing.

• When we first came on the scene, you could walk through (yes, through) the upper-most tier of arches. That was where the water flowed and we followed the course from one side of the river to the other. We even crawled to the very top when we found large blocks of stone that had gone missing. (It was vertiginous, but really cool.)

That is still possible, but you have to pay for a guided tour of the aqueduct. Ask at the information office on site.

• There’s a charming little site nearby, between the Pont du Gard and the museum complex, that is pleasant to walk through. Named the “Memoires de Garrigue,” it explains the agriculture of the Gard region. You’ll learn all about making olive oil and carbon de bois. Excellently signposted. Well worth a stroll.

GETTING THERE:

Take the main route out of Uzes, along its southern corridor (Tour Fenestrelle, rather than Saint Siffret or Lussan) and follow the D981 in the direction of Remoulins. The road will begin to climb gently to a rond point (roundabout) just before you get to the Pont du Gard site. Find a safe and legal place to park (follow the example of others) and take the dirt road that branches off to the right. The remnants of the aqueduct will soon be seen (marked with a red arrow above).

LINKS:

From the Book:

Chapter 24: Ubi Sunt Qui Ante Nos Fuerent

Population levels throughout Europe exploded as a result of these people’s innovativeness. But their civilization, like that of the Paleolithic before it, eventually had to give way to a culture that eclipsed even theirs—that of the mighty Roman empire.

Led by Julius Caesar, the Roman army invaded Gaul in 44 B.C.E. and subjugated the Celtic (as in, neolithic) tribes of France, Belgium and Germany.

But theirs was not to simply be a story of conquest, because conquerors are invariably conquered in turn. The Romans approached it differently. Unlike almost every other tribe and civilization that we are aware of, they took an innovative approach to the peoples they subjugated; which goes a long way to explaining why the Roman empire lasted as long as it did.

The real genius of Rome lay, not in its ability to conquer, but to assimilate. Gauls and members of other conquered groups were allowed to become full citizens of the Empire, enjoying all the rights of native-born Romans. Some even rose to become emperors.

To help “civilize” the newly conquered regions, the Roman state offered retiring soldiers free land in the conquered provinciae (provinces; it is how Provençe gets its name). This policy had a multi-pronged purpose: it populated the region with Roman citizens; spread the influence of the Roman state throughout; and kept highly-trained and potentially troublesome ex-soldiers—who were prone to rioting—far from Rome.

The retirees sent to colonize the Uzeges were members of Rome’s famed 10th Legion, which had defeated Anthony and Cleopatra in Egypt. They were dispatched to Nemausus (now Nimes, a half hour drive to the south of Uzes), and spread out from there.

They left their mark on Saint Siffret. The foundations of several villae have been found along the old Roman road (now the D982) that connected Uzetia with other population centers. And in the hills above St. Quentin la Potterie, a Roman quarry produced millstones of especially durable quality; stone so dense that it was prized throughout southern France. The site is today littered with millstones, some only half-finished, while others remain trapped in the rock.

The Roman Empire also dazzled with its accomplishments. The mind boggles to think what it must have been like to be a simple Gaulish farmer of the time and then walk beneath a massive Roman arch and be confronted with a city a hundred times larger than anything they had ever seen before. Broad, paved streets bustled with traffic. Buildings rose to five and six stories tall. And on the outskirts, there was a colosseum that seated 30,000 spectators, where public fights were put on featuring wild beasts imported from Africa.

Water—an incredibly scarce resource at the time—gushed everywhere. Nemausus had massive fountains, public baths decorated with frescos and mosaics, Olympic-sized swimming pools (heated and unheated), even saunas. Perhaps most impressive, the public bath’s lavatories flushed away human waste, a feature most French homes of the region wouldn’t have for another 1,900 years.

As if that wasn’t impressive enough, the Romans were amazingly talented builders. In the area, no better example of their skill exists than the 24-mile long aqueduct that brought water from Uzes to Nimes, and the Pont du Gard, a magnificent three-tiered bridge that spans the Gardon river is such an amazing feat of construction, and so beautiful, that it has rightly been designated a UNESCO World Heritage site. Every Gaul at the time would have been left slack-jawed with amazement upon seeing it.