Chateau de la Commanderie Home Tour

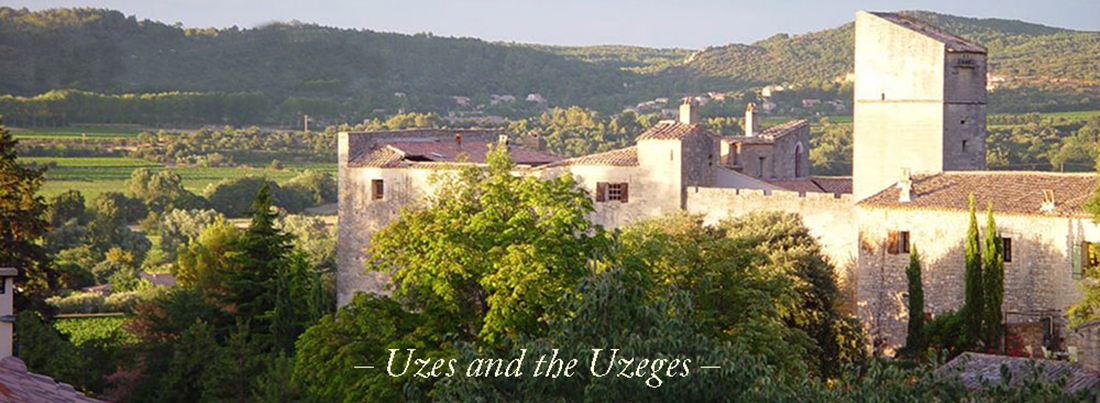

The Chateau de la Commanderie lay in ruin for centuries. Limestone blocks littered the courtyard, making walking through it hazardous. Windows were open to the sky, and roofs had neither tiles nor beams. Uzes was a sleepy backwater at the time. And Saint Siffret barely had more than 600 residents.

Slowly, over time, people began to recognize the beauty of the area. Its unspoiled nature began to draw visitors, then more. And eventually, the rise in ‘green tourism’ grew to the point that a London-based architectural firm purchased the ruin from the French farmer who lived in the valley beneath it and converted the complex into ten private residences.

Take a tour of one with us…

Home entrances in the area can be quite rudimentary, and this one is no different. Opening the front door requires the turning of the lock (in a direction opposite to the way American ones open), the depressing of an upper iron tab,, and the aggressive addition of nudges, pulls, yanks and shoves. Every time the front door opens, it seems to do so reluctantly. Things are not modern…and that’s just fine.

With the exception of the addition of an Oriental rug, the entry looks the same as it did when Linda first entered Jeet and Manfred Mittmann’s home so long ago. An odd coming-together of events had led to their meeting (See: Chapter One, The World’s Most Incongruously Dressed Gardener), and in no time at all, they had become friends.

A day later, the Mittmanns suggested Linda might want to buy their home; an offer that was quickly accepted.

Houses of old France are elegant and beautiful, but can have rough edges. In this instance, the people who rebuilt the castle ruin opted to place a wall where there had not been one before, resulting in the castle’s “Great Room” being split in two—which provided us with exactly with one half of a fireplace. (Living in old French homes is nothing, if not whimsical.)

The thickly-enameled wood-burning stove that had been set into the fireplace seemingly weighs close to 8,000 pounds, and is rusted through and through. A decorative element, thus, that will never warm the room.

The kitchen was the only part of the home that needed extensive remodeling. There was no countertop extension, the sink had holes in it, lights were plastic and fluorescent, and there was little storage space available (a long strip of Provençal material run along a cord hid whatever was stored beneath the counter). Linda wanted the home to reflect the castle’s tradition during the renovation process and chose rustic elements, mandated that appliances had to be hidden behind wooden doors, and selected Andalusian Blue stone, which was quarried from the Pyrenees mountains, for the countertops.

No plastic. Everything had to be stone, metal or wood.

An old fireplace dominates the family room. The crucifix on the mantel reflects the influence of the bishops of Uzes, who owned the castle during medieval times. Sadly, the fireplace was no better at heating the room than the (half) fireplace in the dining area was…so we placed a wood-burning stove in it. Not romantic by any means, but at least efficient.

Modern homes tend to have open plan formats. Secret France home tours feature secluded nooks.

The home is built to an ‘L” shaped, with the smaller end of the letter ending in this room, which leads to the tower. It is through there that the battlements wall, single bathroom, single bedroom and pigeonier at the very top are accessed.

Homes in France have often been built upon during the centuries and can be somewhat cobbled together at times, as with this “stairway,” which is a challenge to walk up, day or night because it is so uneven. S Secret France home tour can be daunting at times (and this says nothing of the constricted passageway that leads to the tower above).

To say that the bedroom is not large is to make a massive understatement. There is room for a double bed, a chair, and one—only one—nightstand. But the atmosphere! The flickering of the candles at night. The way the stone glows during the day. And the roar of the mistral when it strikes the tower!

In medieval times, pigeons—important sources of both protein and fertilizer—were raised in the upper-most room of the tower. Each of the circular cavities that line the room’s four walls represents a pigeon’s nest.

The nests were made of ceramic jars that were set on end, and then had the area around them filled in with plaster.

A machicoulis, an opening through which stones could be dropped on invaders, is built onto the east side of the tower, and the wall alongside displays the remnants of the staircase that lookouts used to climb to the very top of the tower.

It is here that our Secret France home tour ends.

From the Book:

Chapter 14 "Inventory"

That only left the pigeonier to explore. A narrow landing off the bedroom led to a claustrophobically-narrow set of winding stone steps, the ceiling there so low, and the walls closing in so tight, that I had to climb them heavily bent over. It was like passing through a tunnel made of stone: gloomy, dirty, and uncomfortably narrow.

Almost every stone I saw had lost some of its pointing, which left deep voids in which spiders had made their homes. It was impossible not to brush against the cobwebs that gathered along the walls, and I tried hard not to think about what else might be latching onto me as I worked my way upward.

From my reading of history, I knew that tower passages like this always curved to the right, designed that way because most invaders, like most people in the world, were right-handed. This feature meant that the castle’s defenders could thrust and hack away at their besiegers from above, while the attackers found the narrow wall to their right constantly getting in the way of their swordplay.

I finally reached our son’s bedroom, the pigeonier. As the name suggested, this was where the castle’s pigeons had been kept. All four walls were honeycombed with shallow ceramic jars that had been set on end, and then stacked floor-to-ceiling high, the spaces between the jars being filled with rubble and then plastered over so only their openings showed.

Each jar would have been the nesting place for a pair of pigeons, and I began counting them.

“Two hundred and fifteen,” Erik said from his cot, where he lay dozing. “I counted twice.”

That having been done for me, my tour of the castle had ended. I walked over to one of Erik’s windows (larger than ours, I noticed) and looked out.

“Pretty, huh?” our son said from his bed.

I nodded, and ran my mind over all the beautiful things I’d seen that morning. The courtyard, the well, the powerful tower, the crenellated wall. We were incredibly lucky people. The castle was amazingly beautiful, beyond belief, and…

I became aware of the floor. It seemed uneven.

Did our tower have a lean to it? A bad one?