Life in a French Castle

After driving all over the Languedoc province, and dealing with an obstructive realtor who closely resembled a parakeet, we ended up buying a small home in a crusader’s fortress that had been broken up into ten residences by an English architectural firm. The chateau de la Commanderie would teach us what life in a French castle is like: the gorgeous countryside…and its scorpions; the incredibly warm and wonderful people…and not so much so, the governmental tax collectors; the delightful weather…also the mistral and oppressive heat; and best of all, the people.

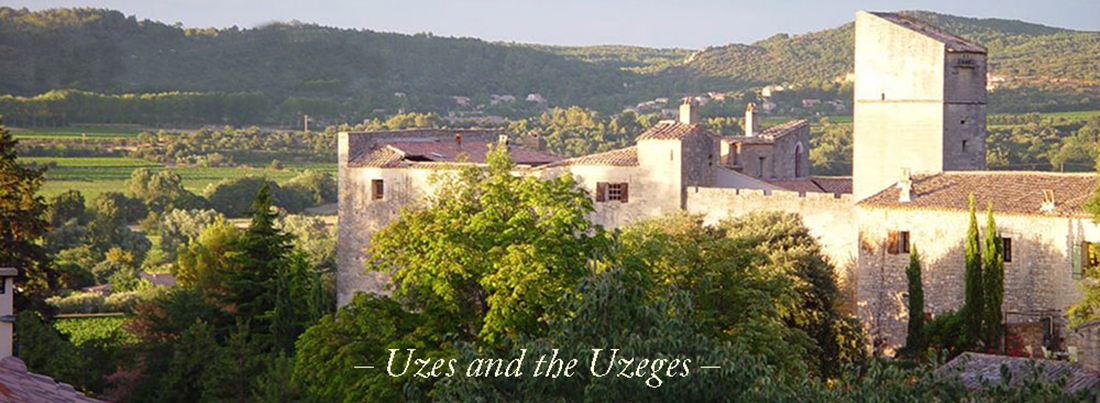

Take a tour of the place with us.

The ‘Commanderie’ in Saint Siffret is reputed to have been built by the Knights Templar, and has experienced all the ravages of French history: from the massacre of thirty Catholic soldiers in its courtyard during the Wars of Religion…to the refuge it represented during the Black Plague years (it was here that the bishops of Uzes fled when the plague devastated the countryside).

This is no fairy tale castle, but a fortress built for fighting. The inner courtyard, however, is a thing of beauty. Saint Siffret’s 12th century Romanesque church anchors the complex to the south, with the medieval well and the dramatic castle tower and gate at the middle.

The well is an amazing thing, and invariably draws everyone’s attention. People can’t help but clamber up its sides to look down.

This is supposedly the place where the bodies of the 30 Catholic soldiers who were killed in the courtyard were dumped after Protestant troops took the castle during one of the Wars of Religion of the 1500s. This is laughably improbable, because the Protestants would never have poisoned their own water source. Life in a French castle, it seems, has to come with its own legends.

The other half of the courtyard connects with the medieval-era tithing barn, which has been converted into a series of charming homes that overlook the vineyard-covered valley below.

When we moved in, the ruine next door was aptly named. The roof lay open to the sky, window openings were bare, and parts of the facade were crumbling. David Green, an eminent architect in London, converted it into the castle’s most sumptuous home. The “ruine” as it is still called today, shares a wall with the village church on one side, and our home at the other.

A number of prehistoric cache pots carved from limestone attest to the very old age of the settlement. Nestled together near David Green’s home, the neolithic (neo: new; lithic; stone age) era remnants are three feet across and equally deep, and are amazingly smooth to the touch. (It is amazing to consider that the people who carved these pots 5,000 to 25,000 years ago only had tools of bone, wood or stone to work with.)

This is not the only neolithic era artifact that can be found at the castle. One year, an archeologist who had just returned from a dig in Corsica, was surprised to find a sacrifice stone standing to the side of the castle gate. Round circles for votives had been cut into the rock, and three channels served to evacuate some form of liquid (which the archeologist felt would most likely be blood).

The home Linda found for us connects with the ruine on one end and the tower on the other. A living area with a raised floor (suggesting it was a place of prominence) spans the room, with a separate area that leads to the stone stairway by which one enters the tower. There, a tiny bathroom, small bedroom, and at the very top, the pigeonier (where the pigeons were kept) may be found.

Note the stone perches and entrance holes for the pigeons, which represented a valuable source of protein and manure during the Dark Ages. The stone ledge immediately below was to prevent rats from climbing to the nesting sites and threatening the pigeon chicks.

No one has been able to come up with an explanation for the three large stones that stick out perpendicular to the house wall. Homes in the Cevennes mountains and the nearby Herault province frequently have homes with this feature. Folklore suggests that the mason was due a glass of wine whenever they reached one, and that the glass was placed on the stone. But that strains credulity. It might just be a decorative feature.

The tower is one of Saint Siffret’s most iconic structures. Built of limestone blocks that were sawn from the ground (it’s true!), the tower’s closely-fitted blocks attest to the quality of its construction.

A crenelated wall with walkway connects with the tithing barn. Each of the beautiful homes within have views of the far-reaching countryside that spill in through their windows: vineyards seemingly without cease; bold yellow slashes that define sunflower plantings; and muted ones of wheat (which fed the revolutionaries during the American War of Independence in 1776)

And just beyond the gates, a village that seems to have been lost in time. Take a tour of it here

From the Book:

Chapter 24: Ubi Sunt Qui Ante Nos Fuerent

The real genius of Rome lay not in its ability to conquer, but to assimilate.

Contrary to standard practice at the time, Gauls and members of other conquered groups were allowed to become citizens of the Empire, enjoying all the rights of native-born Romans. Some even rose so high as to become emperors.

To help “civilize” the conquered regions, the Roman state offered retiring soldiers free land in the conquered provinces (it is how Provence got its name). This policy had a multi-pronged purpose: It populated the region with Roman citizens who spread the influence of the Roman state, and it kept highly-trained ex-soldiers (who were prone to rioting) far from Rome.

The retirees sent to colonize the Uzeges were members of the famed 10th Legion, which had defeated Anthony and Cleopatra in Egypt, and were based in Nemausus (now Nimes, a half hour’s drive to the south of Uzes).

They left their mark. In Saint Siffret, the foundations of several villae have been found along the old Roman road (now the D982) that then connected Uzetia (Uzes) with other population centers. And in the hills above St. Quentin la Potterie, a Roman quarry produced millstones of especially durable quality; stone so dense that it was prized throughout southern France. The site is littered with millstones, some only half-finished, others still trapped in the rock, and Roman pottery shards are strewn across the area.

The Roman Empire also dazzled with its accomplishments. The mind boggles to consider what it must have been like to be a simple Gaulish farmer of the era and walk beneath a massive Roman arch and be faced with a city a hundred times bigger than anything he had ever seen before. Broad streets paved with stone bustled with traffic. Buildings rose to five and six stories in height. And on the outskirts, there was a coliseum that could seat 20,000 spectators, where public fights were put on featuring wild beasts imported from Africa.

And water—a tremendously scarce resource—gushed everywhere. Nemausus had massive fountains; public baths that were lavishly decorated with frescos and mosaics, Olympic-sized swimming pools (heated and unheated); even saunas. Perhaps most impressive, the public bath’s lavatories flushed away human waste—a feature most French homes of the region would not have for another 1,900 years.